Antenatal vital sign assessment – This course is designed to understand the care of pregnant women and newborn: antenatal, intra-natal and postnatal; breast feeding, family planning, newborn care and ethical issues, The aim of the course is to acquire knowledge and develop competencies regarding midwifery, complicated labour and newborn care including family planning.

Antenatal vital sign assessment

Vital sign

Vital signs are measurements of the body’s most basic functions. The 4 main vital signs routinely monitored by healthcare providers include:

- Body temperature

- Pulse rate

- Breathing rate (respiration)

- Blood pressure (Blood pressure is not considered a vit vital sign but tis often measured along with the vital signs.)

Vital signs are useful in detecting or monitoring medical problems. Vital signs can be measured in a medical setting, at home, at the site of a medical emergency, or elsewhere.

Blood pressure

Blood pressure (BP) is the force exerted by the blood on the walls of the blood vessels. It varies within the different blood vessels; it is higher in the large arteries near to the heart, and lower further from the heart within the smaller arteries, arterioles and capillaries. BP continues to reduce as the blood returns to the heart in the venules and veins.

Blood pressure (BP) is measured as millimetres of mercury and recorded as mmHg. (The mercury is in the measuring. column of the BP device). Blood pressure is usually the arterial BP; it is also possible to measure venous BP, but this is usually only done in special circumstances.

- Arterial BP is therefore the pressure exerted on the walls of the arteries. Arterial BP makes the blood flow around the body and therefore allows oxygen to reach all vital organs and tissues. Arterial BP changes during the heart beat cycle: when the ventricles of the heart contract (systole) the BP increases; and when the ventricles relax (diastole) the BP decreases, When BP is taken, you therefore assess both the highest and the lowest levels of pressure. That provides a true picture of the different physiological responses in the heart cycle.

Arterial BP can be recorded in 3 ways:

1. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) the mean, or average, pressure needed to push, the blood through the circulatory system. MAP helps Doctors interpret the changes, in BP. This is usually only done with critically ill women receiving intensive care.

2. Systolic pressure; Is the pressure exerted on the blood vessel walls following the systole or contraction of the ventricle: the arteries contain the most blood then, so the pressure is highest. Systolic pressure is determined by 3 factors:

- The amount tof blood the ventricles eject into the arteries (called the stroke volume);

- The force of that contraction; and

- The distensibility of the artery wall (its ability to stretch or or dilate).

- An increase in the first two factors, or a lessening of the third factor, leads to a raised systolic pressure; and vice versa.

3. Diastolic pressure: Is the pressure exerted on the blood vessel walls during diastole (relaxation) of the ventricle; the arteries contain the least blood during this time, so the least amount of pressure is exerted on the artery walls.

BP is taken as a measure of both the systolic pressure and the diastolic pressure, so it is expressed as 2 figures: systolic/diastolic. So for example: 120/80 mmHg, usually just written as 120/80; or 114/76 etc.

Factors that influence BP include:

- Blood volume (so a loss of blood volume as with a haemorrhage – will result on a decreased BP;

- Heart rate: BP increases with increased heart rate;

- Age; BP increases with age as artery walls get less elastic;

- Day/night variations: systolic BP highest in evening, lowest in morning; changes with rest and sleep;

- weight: overweight people tend to have higher BP;

- Smoking raises BP;

- Eating: BP raises for 30-60 minutes after eating;

- Stress, fear, anxiety all can raise BP by stimulating the sympathetic nervous system;

- Exercise; BP raises for 30-60 minutes after exercising;

- Hereditary factors: if one parent is hypertensive there is 10-20% risk of offspring having raised BP; if both parents have it, risk increases to 25-45%;

- Disease: any disease that affects the hearts stroke volume, the blood vessel diameter, peripheral resistance, or respiration will affect BP.

Equipment:

- Stethoscope and Sphygmomanometer:

Figure: Stethoscope

Figure: Sphygmomanometer

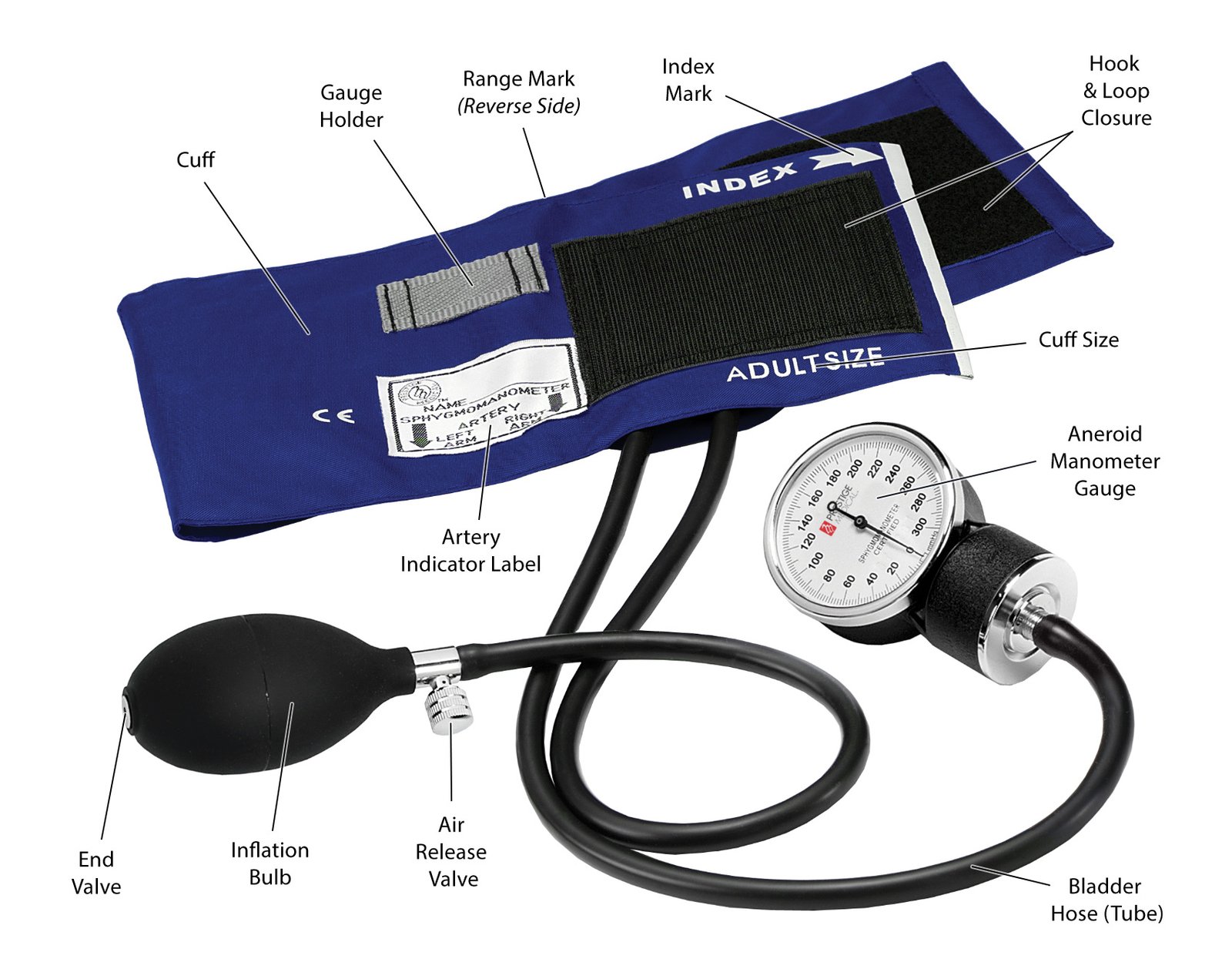

A sphygmomanometer consists of:

- An inflatable cuff to wrap around the arm; with a small rubber bladder in part of the cuff, with a tube and attached bulb used to pump up the bladder, so it will apply external pressure over the artery; with a small control valve to turn, to allow the pressure to gradually decrease.

- A manometer or pressure gauge to measure that pressure. There are several styles of manometer: an aneroid manometer with a circular gauge, with a needle that points to the numbers; a mercury column manometer, which has a column of mercury which rises as pressure is inflated in the cuff, and numbers On the column to read the pressure; or an oscillatory manometer, an electronic machine which measures the BP automatically later is applied.

- All manometers need to be maintained and recalibrated every 6 to 12 months to maintain accuracy. The date of the last calibration should be written on the machine as a reminder.

- Some researchers suggest that lack of calibration means that 20% of hypertension cases are missed, while others are wrongly diagnosed.

- The cuff is placed around the upper part of the arm, wrapped around firmly, and held in place with a Velcro wrapper or by being tucked in. Cuffs usually show a printed range, and when wrapped around the arm the arm must fit within this indicates whether it is the correct size cuff for that sized arm.

- It is important that the correct sized cuff is used, or else change for a smaller or larger cuff as appropriate.

- A cuff that is too small can give a falsely high reading

- A cuff that is too large can give a falsely low reading.

Description of how BP is measured:

The cuff is wrapped around the limb where BP is to be taken; a measured pressure on the artery (usually the brachial artery) is caused by inflating the cuff, by rhythmically squeezing the bulb. This pressure in the cuff occludes the blood flow through the artery at that point. The pressure is slowly released, by gently adjusting the control knob of the bulb. As the pressure is released, the blood begins to flow through the artery again, and the sounds of it can be heard with the stethoscope placed over the artery.

When the first sound is heard, whichever number the manometer gauge is at/pointing at, is the upper figure of the BP, the systolic pressure. The pressure in the cuff continues to be slowly released. When the cuff is no longer impeding the blood flow, the sounds stop, and whichever number the manometer gauge is at/pointing at, is the lower figure of the BP, the diastolic pressure.

Korotkoff sounds:

- When listening to these sounds there are a range of sounds heard; they are named Korotkoff sounds, after the person who first described them as 5 sounds

- The first figure of the BP (the systolic pressure) is taken as being Korotkoff I, the first faint tapping sounds that increase in intensity.

- The sounds change, until Korotkoff IV is a soft muffled sound, and Korotkoff V is silence – no sounds heard.

- There has been some debate about which sound to listen to; but diastolic BP is generally taken as being Korotkoff V silence. However, if the silence goes all the way down to zero mmHg, then Korotkoff IV sound is taken as the diastolic BP.

Procedure for taking BP:

- Obtain informed consent make the woman comfortable; if she has been active let her rest for at least 5 minutes;

- Assist woman to suitable position, sitting or resting, no tight clothing on left upper arm;

- Collect equipment: stethoscope, sphygmomanometer;

- Wash and dry hands;

- Position sphygmomanometer so base of manometer is level with the woman’s heart, if possible. You sit, if necessary, so that your eyes will be level with the needle position or mercury level of the manometer.

- Ask woman to uncover her upper arm, and support her arm with the palm turned up;

- Palpate the brachial artery (see Resource FM 39 – Site of adult pulse assessment);

- Position the cuff with the lower edge 2-3 cms above the site, with the bladder of the cuff centered over the artery; close the control valve.

- Palpate the brachial artery with the fingertips of one hand and feel the pulse; then with your right hand (if you are right hand dominant) pump the bulb and inflate the cuff over the artery until the pulse can no longer be felt. Continue to inflate the cuff for 30 mmHg above that point

- Open the valve slowly and let the cuff deflate slightly, taking note of when the pulse reappears: that is approximately the systolic pressure. Then deflate the cuff quickly, by opening the control valve completely.

- Wait at least 30 seconds then close the valve.

- Place the stethoscope earpieces in your ears, and with your non-dominant hand (? left hand) hold the head of the stethoscope over the brachial artery where you palpated the pulse.

- Again inflate the cuff, this time straight away to that pressure 30 mmHg above the palpated approximate systolic pressure.

- Use the control valve to slowly deflate the pressure at 2-3 mm per second, listening for the first clear sound you can hear in the stethoscope (Korotkoff I sound);

- Read the needle position or mercury level of the manometer where the sound was first heard, and note the number to the nearest 2 mmHg; remember it;

- Continue to slowly deflate the cuff until the sounds are no longer heard (Korotkoff V sound); note that level on the manometer to nearest 2 mmHg; again remember the number.

- Deflate the cuff completely, remove it; make the woman comfortable again.

- Document and record the result in the appropriate place.

- Share and discuss the finding with the woman.

- Report or take action on the result if it is outside of normal range.

- There are some factors that affect the accuracy of threading;

Normal value blood pressure range

- The normal range for arterial BP in a healthy adult is 100-140 mmHg systolic pressure/60- 90 mmHg diastolic pressure. This does vary according to age and other factors though.

Significance of variation of rate:

- Hypertension or high blood pressure is defined as a systolic BP of 140 mmHg or more and a diastolic of 90 mmHg or more,

- Hypotension (low BP) is defined as when the systolic BP is less than 100 mmHg.

- Maternal deaths from pre-eclampsia and eclampsia,

- pregnancy disorder which includes high BP, are the second greatest direct cause of maternal mortality. Therefore it is very important that midwives detect BP problems early so that the woman can be referred for appropriate care. If she has appropriate care and intervention, both mother and fetus/baby’s lives may be saved.

Changes associated with childbirth:

- pregnancy, there are haemodynamic changes as a result of hormonal and anatomical changes. These changes result in an increased blood volume, increased cardiac output, and increased heart rate. In an adult who was not pregnant, these changes would mean a raise in BP. But in pregnancy, these changes are countered by the effect of progesterone relaxing the blood vessel walls, and thus reducing peripheral resistance.

- BP therefore usually decreases in the first trimester, and begins to rise gradually from the middle of pregnancy, and returns to pre-pregnancy levels by term.

- This early decrease is much less for systolic pressure than for diastolic pressure. Systolic pressure reduces by 5-10 mmHg, and diastolic by up to 10-15 mmHg

- Some women experience supine hypotension syndrome, due to the weight of the pregnant uterus compressing the inferior vena cava, affecting venous return. This occurs more conunonly when the woman is supine, and corrects if she changes to a lateral or recumbent position. Therefore it is best if women are not laid flat on their backs in pregnancy or labour.

- In labour, anxiety and pain can lead to a rise in BP.

- Also, during contractions, both systolic and diastolic pressure increases during contractions; they return to normal when the contraction has finished. Therefore only take BP between contractions in labour.

- Following the birth there is increased venous return, so higher venous pressures. As the blood volume and physiological changes of pregnancy decrease; BP returns to its non- pregnant level.

Assessing blood pressure in baby:

- BP is not generally measured for well, term babies

- However, preterm babies are unable to tolerate fluctuations in BP, as it can lead to intracranial haemorrhages, so BP is assessed in babies in special care units.

- In those cases, the BP cuff is placed around either the babies arm or leg.

- BP in babies varies with birth weight, and body weight. While systolic and diastolic pressures can be measured it is usually reported as the mean arterial pressure.

Pulse

The pulse is the direct indicator of the t action of the heart. Each pulse beat is the rhythmic 10 movement (expansion andrecoil) of the arteries as the heart’s left ventricle pumps entricle pumps blood into the circulation.

Equipment:

The fingers are used to assess the pulse; no special equipment is needed to assess the nulse although a watch with a second hand is needed for counting the rate.

Procedure:

- Obtain consent; ensure the woman is comfortable

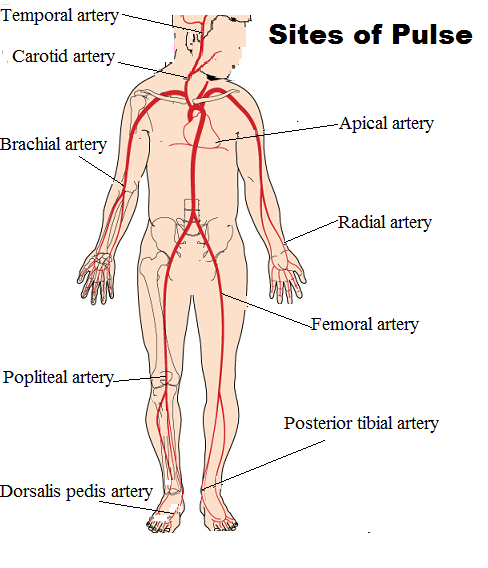

- Select a site: a pulse can be felt anywhere in the body where an artery is near to the surface and can be palpated against bone

- The most commonly used site for taking adult pulse is the radial artery, felt just above the wrist.

- Position the woman’s wrist and arm across her chest with the arm bent at the wrist (read the next section on respirations to learn why it is best to use that arm position),

- The midwife places her index and middle fingers gently in the groove of the woman’s wrist just above the thumb; the fingers are moved along that groove until the pulse is felt. Start with gentle pressure, but the pressure may need to be increased or decreased. If the pressure is too firm the pulse is occluded; if too soft, it is hard to feel the pulse.

- When the pulse is clearly identified, count the pulse for 30 seconds if it is completely regular and then double that number to determine the rate per minute (beats per minute,

or bpm). If the pulse is irregular or slow, count for 60 seconds, - Also note the regularity of the rhythm, and the amplitude. The pulse rhythm is normally steady and regular; but it may be irregular or have extra beats.

- Amplitude is the feeling of strength of the pulse beat; it is usually described as normal, Weak or thready orrapid, full and bounding.

- Without moving your fingers or the woman’s arm, discreetly count the respirations also (see next section). Document and record the result in the appropriate place.

- Report or take action on the result if it is outside of normal range.

- Another way of counting the heart rate is by using a stethoscope to listen to the heart.

- ECG or pulse oximeters also give a heart rate reading.

Normal value range:

- A normally healthy woman’s heart rate is approximately 65 – 85 beats per minute (bpm); some researchers suggest 60-100 bpm.

- The pulse rhythm is normally steady and regular.

- Amplitude is the feeling of strength of the pulse beat; should be ‘normal’ not weak or thready, rapid, full or bounding.

Significance of variation of rate or rhythm:

- Changes in the heart rate and respiratory rate are the earliest and most sensitive indicator of deterioration of wellbeing.

- Tachycardia describes an abnormally fast heart rate above 100 bpm;

- Factors that cause increased heart rate include: infection, fever, pain, haemorrhage, shortage of red blood cells (haemorrhage or anaemia), fluid or electrolyte imbalance including dehydration, allergic reactions, some diseases (e.g. hyperthyroidism), some medications (e.g. Salbutamol), exercise, strong emotions stress, anxiety, excitement; pregnancy (see below).

- Bradycardia is a slow heart rate, below 60 60 or 50 bpm.

- Factors that reduce the pulse rate rate include: rest and relaxation, good exercise tolerance in athletes, hypothermia, and some health issues e.g. myocardial infarction.

- Irregular pulse rhythm indicates an irregular pumping action of the heart,

- Amplitude that is weak or thready may be due to hypovolaemia; amplitude that is full and bounding may be due to infection.

Changes associated with childbirth:

- In pregnancy, from 7 or 8 weeks gestation, maternal heart rate increases by 10 – 20 bpm due to changes in cardiac output and stroke volume, and the increase in total blood volume. This increase peaks about 32 weeks, and declines slightly in the third trimester.

- Mild cardiac arrhythmias may occur as a result of these cardiovascular changes if pregnancy. These are usually harmless, and resolve without treatment.

- However if a pregnant woman has pre-existing cardiac di disease, or develops it in pregnancy, this can place additional and dangerous stress on her cardio-vascular system. Careful cardiac and obstetric care is needed for these women, or death could result.

- In labour each uterine contraction returns 300 500 mis blood to the circulation. The heart rate therefore rises; but this might also be due to pain, anxiety, or exercise (from uterine contractions).

- There is cardiac instability in the postpartum period, with an increase then decrease in pulse, due to changes in circulation with the loss of the placenta, blood loss at the birth, and compensatory mechanisms. By 1 hour after birth cardiac output has returned to pre- labour values. By 6 to 8 weeks postpartum, hormonal and other changes to the cardiovascular system have returned to normal; and by 12-24 weeks cardiac output has returned to pre-pregnancy rates.

Assessing heart rate in baby:

- The usual site for assessing pulse rate in a baby is the apical pulse at the heart; as this is most accurately counted.

- If that site is not accessible, the brachial pulse is the is the next choice; this is ion the inner side of the crease of the elbow.

- A newborn baby has a heart rate of 110-160 bpm.

- A baby’s heart rate varies with respiration, so it is important to count for 1 minute

Sites of taking pulse

[Ref-DMW, Lesson Plan Volume 1, page-59-62]

Respiration

Respiration, breathing, is the way the body gains oxygen, and excretes carbon dioxide. Assessment of respiration includes counting the rate of respirations per minute, as well as assessing the depth of respirations (normal or shallow breaths), and any associated signs such as skin colour (looking for normal healthy colour, or cyanosis).

Equipment:

No special equipment is needed for measuring the respiration rate, but a watch with a second hand is needed needed for counting.

Procedure:

- This is one of the very few tinies when consent is not obtained; this is because knowing your breathing is being observed could lead to a change in breathing pattern. Rather consent is obtained for taking the pulse, and then respirations are also counted in the same procedure.

- Therefore, when taking the pulse, support the woman’s wrist near or across the chest. The rise and fall of the chest can then be discreetly noted and counted for 60 seconds, thus giving a respiration rate per minute.

- Also note other factors such as sounds, regularity, symmetry, depth of respirations; and observe for signs of increased respiratory effort such as nasal flaring, pursed lips, use of accessory muscles in the neck or chest, and any audible cough or wheeze.

- Document and record the result in the appropriate place.

- Report or take action on the result if it is outside of normal range

Normal value range:

- Normal respiration rate range for an adult at rest is 12 20 respirations per minute; although some researchers suggest 10-20, or 12-18 as normal.

Significance of variation of rate:

- Changes in the respiratory and heart rate are the earliest and most sensitive indicator of deterioration of wellbeing.

- Tachypnoea is the term used for raised temperature.

Changes associated with childbirth:

- In pregnancy, both woman, and fetus require oxygen. Progesterone relaxes the smooth muscle of the alveoli, and despite the diaphragm being pushed upwards by the growing uterus, each breath is deeper, but the rate is unchanged.

- In labour, strong and frequent contractions affect the pattern and depth of respirations. Oxygenation must be maintained, so breath-holding or hyperventilation should be discouraged. Women should be supported and encouraged to breathe slowly and deeply; breathing exercises such as this in labour can be helpful to the woman both physically and psychologically.

- Postnatally, respiration quickly returns to its pre-pregnancy volume and pattern.

Assessing respirations in baby:

- When assessing baby’s respiration rate, consent is obtained from the parent’s; make sure baby is calm first.

- Respiration in babies can be erratic, so it is best to expose the chest and abdomen, and observe and count directly for 60 seconds.

- Normal respiration for a newborn baby (who is calm and settled) is 40 – 60 respirations per minute.

- Again, carefully observe for signs of increased respiratory effort / respiratory distress: nasal flaring, grunting, or use of accessory muscles such as sternal, subcostal or intercostal recession or retraction.

Temperature

Body temperature is the balance between heat gain and heat loss, and the body normally maintains a fairly steady core temperature whatever the day’s temperature.

Equipment;

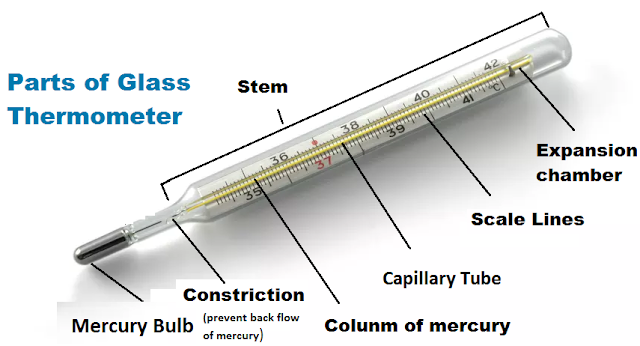

A thermometer is used to measure body temperature. There are several types of thermometer. A they are shared between users, they must be cleaned, usually with alcohol wipe before use, to avoid cross-infection.

- Mercury thermometers: these are no longer being used in some countries, as vapour from the mercury could be toxic if the thermometer is broken. If used, care must be taken when handling them, and if accidentally broken, the mercury must be carefully collected and disposed of

- Digital or electronic thermometers: run on battery, press to start. Follow instructions for individual thermometer for when to begin use, and when to read. Usually takes about

minute, and beeps’ when ready to read result - Tympanic thermometers are special ones which rest in the ear canal to record the tympanic temperature; or strip thermometers which are pressed against the forehead

Procedure:

- Discuss procedure and gain consent.

- Select suitable and safe site to take the temperature;

- For adults, may also use axilla, or mouth with the thermometer tip under the tongue, and the mouth closed gently. In labour, it may be safer to use the axilla site. If using mouth, make sure no food or hot or cold drinks taken recently.

- Clean thermometer with alcohol wipe;

- Prepare the thermometer (shake mercury down to bulb; or press digital thermometer on and wait for signal to start);

- Place thermometer, and hold in place or ask woman to hold as appropriate;

- Wait recommended time, remove the thermometer and read.

- Document and record the result in the appropriate place

- Report or take action on the result if it is outside of normal range.

Normal temperature value range

- The normal temperature range for adults is 35.8 to 37.3 degrees Celsius.

Significance of raised temperature:

- External factors such as digesting a meal, having a hot

- bath, or increased muscular activity may cause a slight elevation of temperature, but this increase is just for a, short time after the event.

- Febrile or fever are the terms associated with raised | temperature.

- The usual reasons for a fever are infection, inflammatory response, or dehydration.

Changes associated with childbirth:

- In pregnancy the temperature may increase by 0.5 degrees due to increased metabolism.

- In pregnancy the fetus is about 8 degree higher than the maternal temperature. A raised maternal temperature therefore means a higher, fetal temperature, associated with hypoxia, fetal tachycardia, teratogenesis, and preterm labour.

- In labour a rise in temperature can indicate infection, dehydration, or as a result of increased muscle activity from uterine contractions. It is sometimes associated with use of epidural anaesthesia.

- Postnatally, some women have a transient rise in temperature in the first 24 hours, perhaps related to the stress of labour and dehydration; that would resolve spontaneously however, and must not ust not be confused with temperature rise due to infection or inflammatory response such as deep vein thrombosis (DVD)

Assessing temperature in baby:

- For baby, the safest site is to hold the thermometer in place under the baby’s axilla.

- Normal temperature for a baby is between 36.5 and 37 degrees Celsius.