Today our topic of discussion is ” Chemical Digestion and Absorption: A Closer Look “.The digestive system is a remarkable and intricate network of organs and processes responsible for breaking down the food we consume into its basic components, which our bodies can then absorb and utilize for energy, growth, and repair.

A pivotal aspect of this system is chemical digestion, which occurs in various stages along the gastrointestinal tract, facilitating the transformation of complex macronutrients into simpler substances for absorption. In this comprehensive article, we will explore the intricate processes of chemical digestion and nutrient absorption in the human digestive system.

Chemical Digestion and Absorption: A Closer Look: The Digestive System

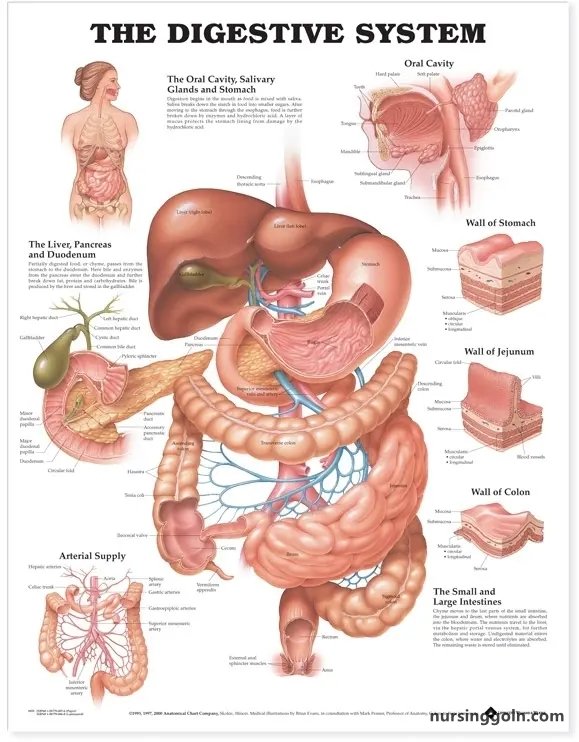

1. Chemical Digestion in the Mouth: The First Bite

The process of digestion begins with the first bite. While the mechanical breakdown of food through chewing is the initial step, chemical digestion also commences within the mouth. Saliva plays a crucial role in this early stage.

a. Salivary Glands and Saliva

Salivary glands, including the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands, produce saliva, a watery fluid that contains various components essential for chemical digestion:

b. Enzymes in Saliva

- Amylase: Amylase is an enzyme responsible for the digestion of carbohydrates. It breaks down complex carbohydrates (starches) into simpler sugars, primarily maltose.

- Lingual Lipase: This enzyme aids in the digestion of fats, although its activity is limited in the mouth due to the acidic environment of the stomach.

c. Mucus and Lubrication

Saliva contains mucus, which serves to moisten and lubricate food, making it easier to form into a bolus that can be swallowed.

2. The Journey through the Esophagus: Mechanical Transition

After the food is adequately masticated and mixed with saliva in the mouth, it is formed into a bolus and transported to the stomach through the esophagus. The esophagus primarily plays a mechanical role in this journey, facilitating the movement of food from the mouth to the stomach through peristalsis, a series of coordinated muscular contractions.

3. Stomach: Where Chemical Digestion Intensifies

Upon reaching the stomach, food encounters a unique and robust environment designed for digestion. The stomach plays a central role in both mechanical and chemical digestion. The gastric glands of the stomach secrete gastric juice, a highly acidic fluid that kick-starts several vital chemical processes:

a. Gastric Juice

- Hydrochloric Acid (HCl): The stomach’s chief cells secrete hydrochloric acid, which creates an acidic environment with a pH of around 2. This low pH serves multiple crucial functions:

- Activates pepsinogen to its active form, pepsin, which digests proteins.

- Facilitates the breakdown of connective tissues in meat.

- Kills potentially harmful microorganisms that may be present in ingested food.

- Pepsin: Pepsin is a protein-digesting enzyme. It cleaves proteins into smaller peptide fragments, initiating protein digestion.

- Mucus: The stomach is lined with a protective layer of mucus that guards against the corrosive effects of HCl and pepsin. Without this protective layer, the stomach’s acid and enzymes could damage its lining.

b. Mechanical Digestion

The muscular walls of the stomach undergo rhythmic contractions, creating a churning action that mixes food with gastric juice. This process gradually breaks down food into smaller, more manageable particles, forming a semi-liquid substance known as chyme.

c. Formation of Chyme

As the mechanical and chemical processes unfold, the stomach gradually transforms the food into chyme, a semi-liquid mixture that is easier to handle and suitable for further digestion in the small intestine. Chyme is the product of mechanical churning, the action of gastric juice, and the breakdown of proteins and other macronutrients.

4. Duodenum: A Hub of Digestive Activity

The duodenum, the first segment of the small intestine, is a vital location for chemical digestion. When chyme enters the duodenum from the stomach, it triggers a cascade of digestive events.

a. Bile and Bile Ducts

- Bile Production: The liver produces bile, a greenish fluid that plays a crucial role in the digestion and absorption of fats.

- Bile Storage: Bile produced by the liver is stored in the gallbladder until needed.

- Bile Release: When chyme enters the duodenum, especially when it contains fats, the gallbladder contracts and releases bile into the duodenum.

b. Pancreatic Secretions

The pancreas, an accessory organ of digestion, plays a pivotal role in the duodenum’s digestive processes. It releases pancreatic juice, a fluid rich in enzymes, into the duodenum through the pancreatic duct.

c. Enzymes in Pancreatic Juice

- Amylase: Pancreatic amylase complements the action of salivary amylase, continuing the digestion of carbohydrates into simpler sugars.

- Lipase: Pancreatic lipase is crucial for the digestion of fats. It breaks down triglycerides into fatty acids and glycerol.

- Proteases: Pancreatic proteases, such as trypsin and chymotrypsin, are responsible for the digestion of proteins, cleaving them into smaller peptides and amino acids.

- Nucleases: These enzymes digest nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) into their individual nucleotide components.

d. Activation of Enzymes

Many enzymes in pancreatic juice are secreted in an inactive form and need to be activated in the duodenum. For example, trypsinogen, an inactive form of trypsin, is converted into its active form, trypsin, in the presence of an enzyme called enterokinase, which is located in the brush border of the duodenum.

e. Brush Border Enzymes

The brush border of the small intestine’s lining contains several enzymes that further digest nutrients. For example:

- Disaccharidases: Enzymes like sucrase, maltase, and lactase break down disaccharides (sucrose, maltose, and lactose) into their constituent monosaccharides (glucose, fructose, and galactose).

- Peptidases: These enzymes continue to break down small peptides into individual amino acids.

5. Nutrient Absorption in the Small Intestine

The small intestine is the primary site for nutrient absorption in the digestive system. As chyme travels through the small intestine, nutrients are absorbed through the intestinal lining and transported to the bloodstream.

a. Carbohydrate Absorption

- Monosaccharide Absorption: Monosaccharides, such as glucose, fructose, and galactose, are absorbed directly into the bloodstream through the lining of the small intestine.

b. Protein Absorption

- Amino Acid Absorption: Amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, are absorbed into the bloodstream through the intestinal lining.

c. Fat Absorption

- Micelle Formation: Bile salts emulsify fats, breaking them into smaller droplets. These micelles transport fats to the surface of the enterocytes (lining cells of the small intestine) for absorption.

- Lipid Absorption: Fatty acids and monoglycerides, the products of fat digestion, are absorbed into the enterocytes. Within the enterocytes, they are reassembled into triglycerides, which combine with other lipids and proteins to form chylomicrons. Chylomicrons are then transported to the lymphatic system before entering the bloodstream.

d. Vitamin and Mineral Absorption

The small intestine also absorbs various vitamins (e.g., fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K) and minerals (e.g., iron, calcium, magnesium) into the bloodstream.

e. Water and Electrolyte Absorption

The small intestine absorbs water and electrolytes, helping to maintain fluid balance in the body.

f. Nutrient Transport to the Liver

After absorption, nutrients pass through the portal vein, which carries them to the liver for processing and distribution throughout the body.

6. The Role of the Large Intestine

The large intestine, also known as the colon, is primarily responsible for reabsorbing water and electrolytes from undigested food material, forming and storing feces, and facilitating the elimination of waste.

a. Fermentation in the Large Intestine

The large intestine houses a complex community of microorganisms, the gut microbiota, which plays a vital role in fermenting undigested carbohydrates. This fermentation process produces gases, such as carbon dioxide, methane, and hydrogen, which can lead to flatulence or gas production in the digestive system.

b. Water and Electrolyte Absorption

The large intestine is essential for the reabsorption of water and electrolytes, helping to maintain proper hydration and control stool consistency.

c. Formation and Storage of Feces

As undigested material travels through the large intestine, water and electrolytes are absorbed, forming feces. Feces are temporarily stored in the rectum before elimination.

d. Elimination

The large intestine plays a critical role in the process of waste elimination. When the rectum becomes full, stretch receptors signal the brain, leading to the urge to defecate. The anal sphincters then relax, allowing the passage of feces through the anus and out of the body.

7. Disorders and Conditions of Chemical Digestion and Absorption

Several disorders and conditions can affect the process of chemical digestion and nutrient absorption, including:

- Malabsorption Syndromes: Conditions like celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, and chronic pancreatitis can lead to malabsorption of nutrients.

- Food Allergies and Intolerances: Some individuals may experience adverse reactions to certain foods, leading to symptoms like diarrhea, abdominal pain, or gas.

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): GERD is a condition where stomach acid flows back into the esophagus, causing heartburn and discomfort.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): IBD encompasses chronic inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal tract, including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): IBS is a chronic condition characterized by abdominal pain, bloating, and changes in bowel habits. It does not cause structural damage to the intestines but can significantly affect a person’s quality of life.

8. Maintaining Digestive Health

To maintain digestive health and support the processes of chemical digestion and nutrient absorption, it is essential to:

- Consume a balanced diet: A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and whole grains provides essential nutrients for proper digestion.

- Stay hydrated: Proper hydration supports the absorption of water and electrolytes in the digestive system.

- Manage stress: Chronic stress can negatively impact digestive health, so stress management techniques are crucial.

- Regular exercise: Physical activity supports overall health and digestive function.

- Avoid overconsumption: Overeating can strain the digestive system, leading to discomfort and indigestion.

Chemical digestion and nutrient absorption are fundamental processes in the digestive system, enabling our bodies to extract essential nutrients from the food we consume. From the moment we take our first bite to the final absorption of nutrients in the small intestine, a series of complex chemical reactions occur to break down macronutrients into their simplest forms. These nutrients are then absorbed through the lining of the small intestine and transported to the bloodstream, ready to fuel our bodies and support their growth and maintenance.

Understanding the intricacies of chemical digestion and absorption is vital for appreciating the critical role these processes play in maintaining our overall health and well-being. As we delve into the inner workings of the digestive system, chemical digestion and absorption emerge as the core processes that ensure our bodies receive the nourishment they require for optimal functioning.