Today our topic of discussion is ” Development of the Male and Female Reproductive Systems “. The development of the male and female reproductive systems is a complex, meticulously timed, and finely tuned process that begins during embryonic life and continues into adolescence.

This developmental journey is not only crucial for individual survival but also for the propagation of the species. This article will delve into the embryological origins of both systems, the influence of genetic and hormonal factors on their differentiation and maturation, and the physiological nuances that distinguish the male from the female reproductive system.

Development of the Male and Female Reproductive Systems : The Reproductive System

Embryological Origins

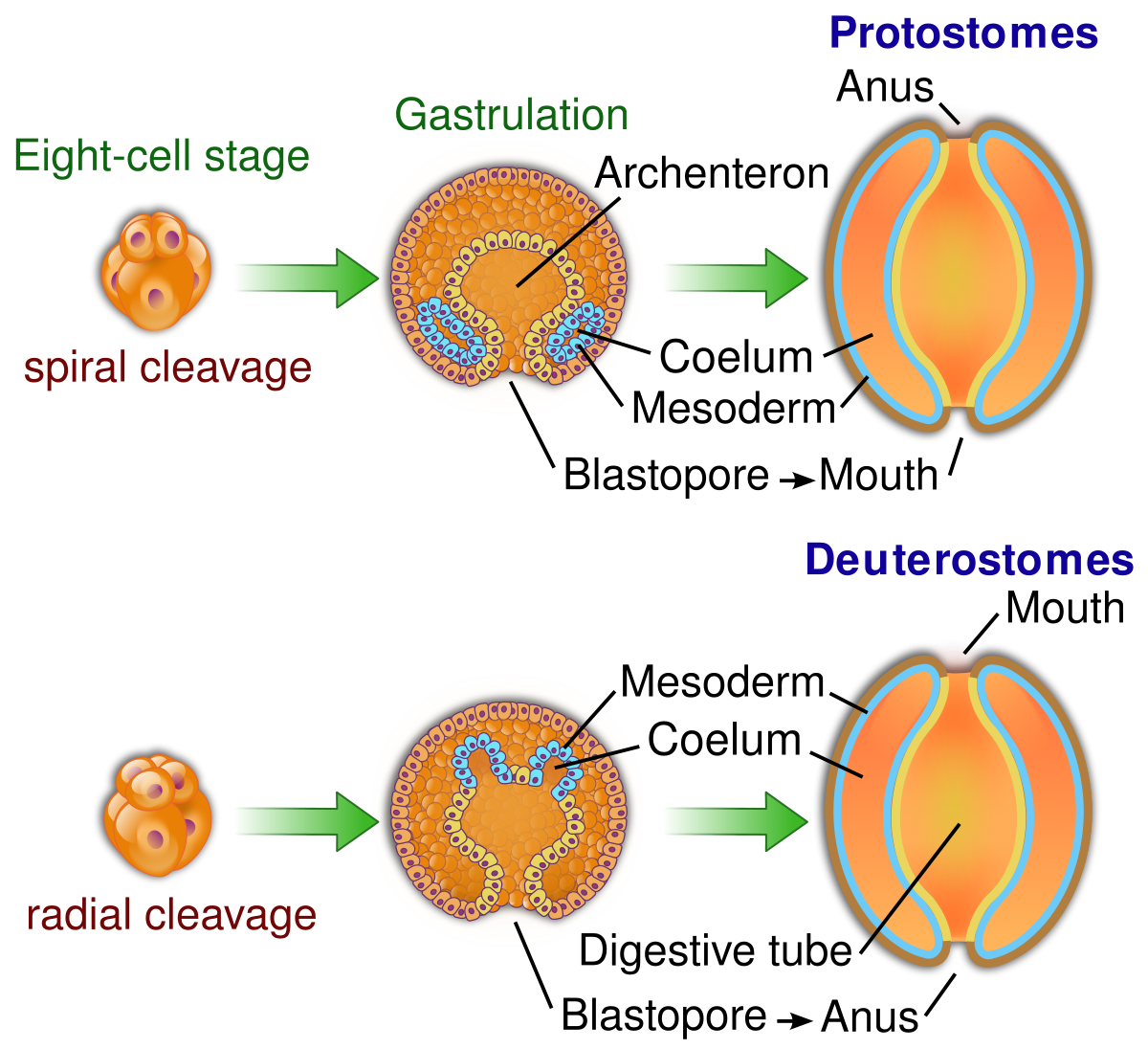

Both male and female reproductive systems originate from the same embryonic tissues, making their initial development quite similar. Around the third week of gestation, the mesoderm (one of the three germ layers) forms the urogenital ridge. This structure gives rise to the gonads, which will become either testes or ovaries, depending on genetic factors—specifically the presence or absence of the SRY gene on the Y chromosome.

In the absence of SRY (typically in individuals with two X chromosomes), the gonadal ridge develops into ovaries. In contrast, the presence of SRY (usually in individuals with one X and one Y chromosome) triggers the differentiation of the gonadal ridge into testes.

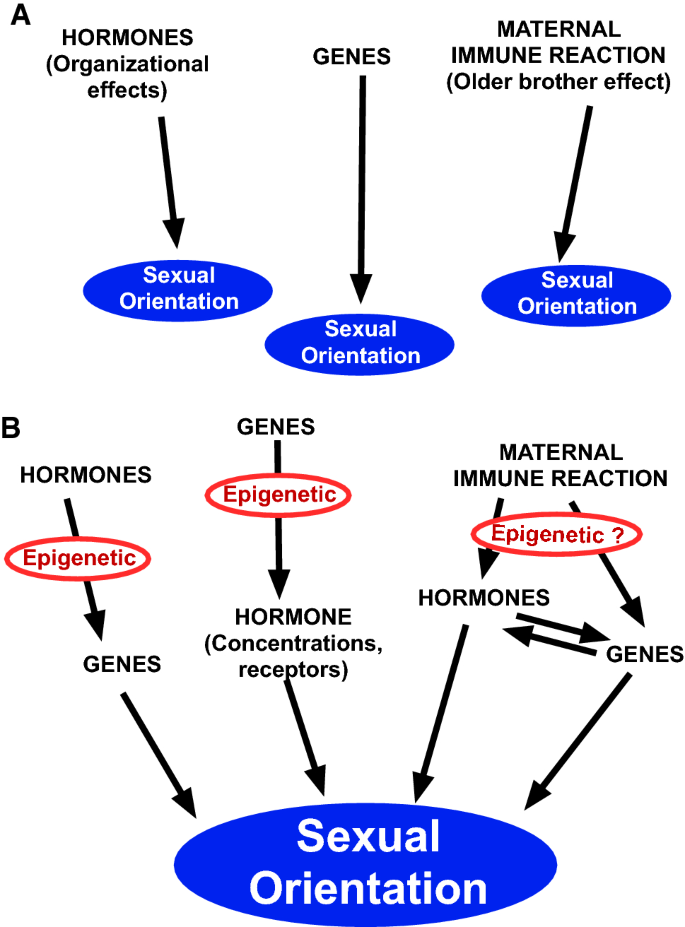

Genetic and Hormonal Factors

The SRY gene encodes the testis-determining factor (TDF), which initiates a cascade of gene activations that lead to testicular development. In the absence of SRY, the gonadal ridges are free to follow the default pathway towards ovarian development. However, several other genes, such as WNT4, RSPO1, and FOXL2, play crucial roles in ovarian development and maintenance.

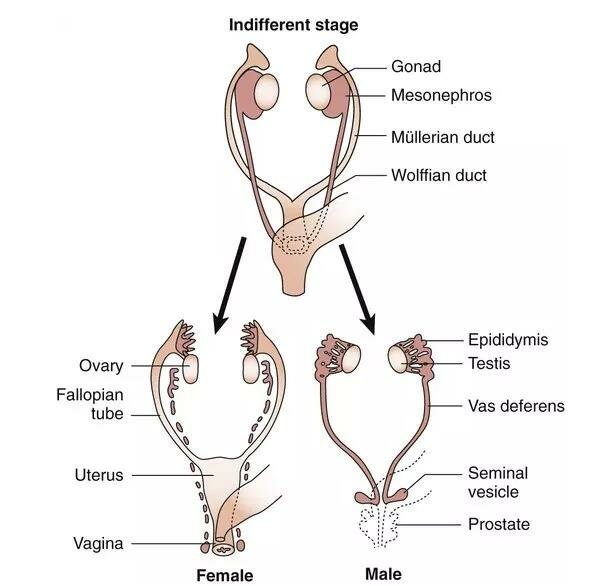

Beyond genetics, hormones significantly influence the differentiation of the reproductive tracts. Testosterone, secreted by the Leydig cells of the testes, drives the development of the male internal genitalia, while Müllerian-inhibiting substance (MIS), also known as anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), secreted by Sertoli cells, leads to the regression of the Müllerian ducts, which would otherwise develop into female internal structures.

Internal Genitalia Development

The internal duct systems for both sexes begin as two pairs of ducts: the Wolffian ducts (male) and the Müllerian ducts (female). In males, the secretion of testosterone and MIS ensures the Wolffian ducts develop into the epididymis, vas deferens, and seminal vesicles, while the Müllerian ducts regress. In females, the absence of these hormones allows the Müllerian ducts to develop into the fallopian tubes, uterus, and the upper portion of the vagina.

External Genitalia Differentiation

External genitalia initially appear the same in both sexes, termed the genital tubercle, urogenital folds, and labioscrotal swellings. However, under the influence of androgens, these structures masculinize to form the penis, scrotum, and associated anatomy in males. In females, the absence of high levels of androgens allows these structures to develop into the clitoris, labia minora, and labia majora.

Descent of Gonads

In males, the testes descend from the abdominal cavity into the scrotum, guided by the gubernaculum and influenced by hormonal and mechanical factors. This descent is crucial as it provides a cooler temperature necessary for spermatogenesis. In females, the ovaries also descend but remain within the pelvis, anchored by the ovarian ligament.

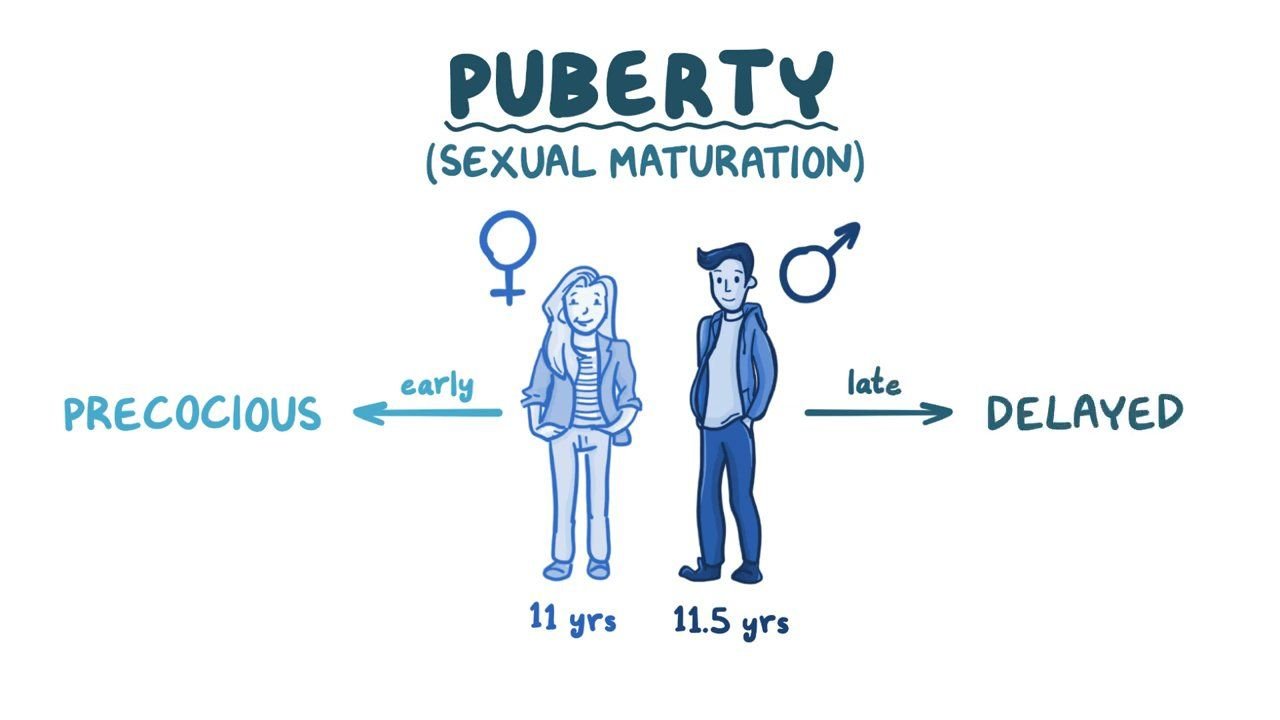

Puberty and Maturation

The maturation of the reproductive systems, which occurs during puberty, is prompted by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. In both sexes, the hypothalamus releases gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which stimulates the pituitary to release luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

In males, LH stimulates testosterone production from the Leydig cells, and FSH promotes spermatogenesis alongside testosterone. The full development of secondary sexual characteristics, like body hair, muscle mass increase, and deepening of the voice, are testosterone-dependent.

In females, LH and FSH regulate the menstrual cycle, stimulate ovulation, and promote the maturation of the oocytes. Secondary sexual characteristics, such as breast development and body fat redistribution, are primarily estrogen and progesterone effects.

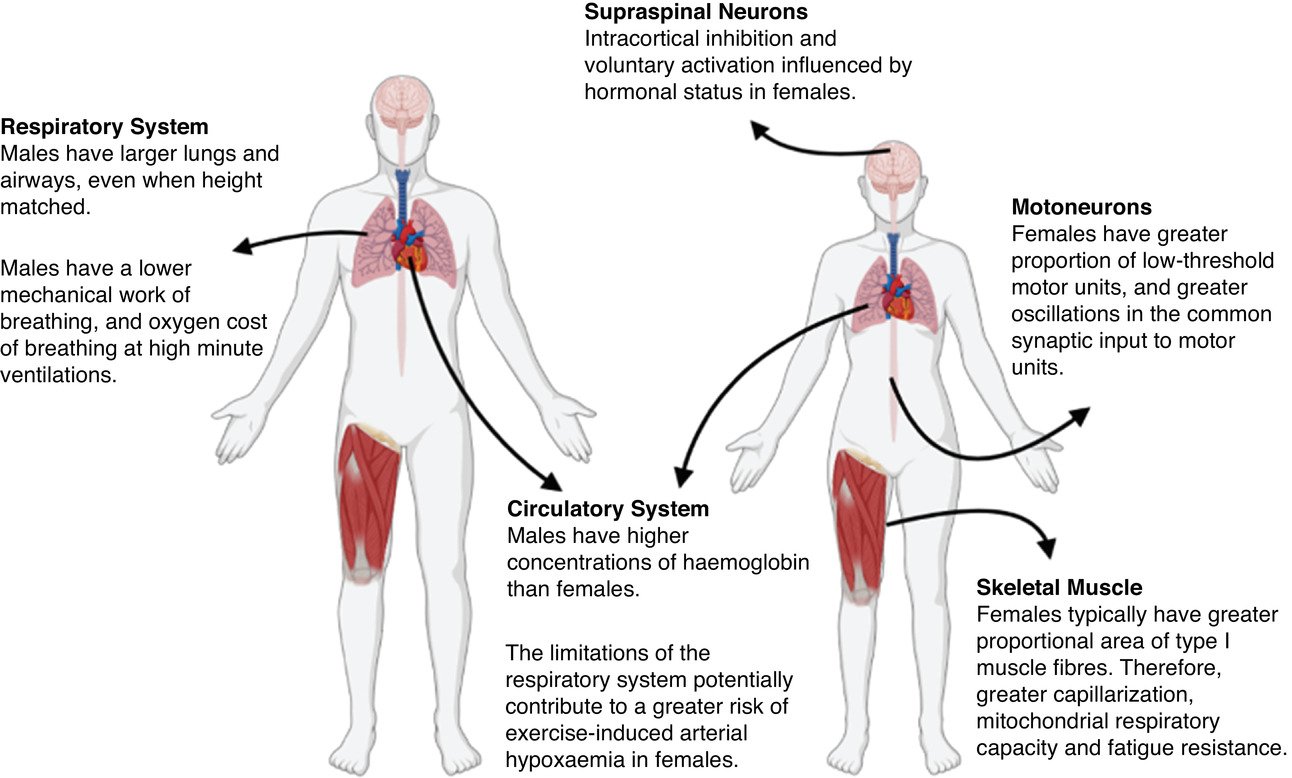

Physiological Differences

The mature male reproductive system is designed for continuous sperm production and delivery. Testes produce sperm in the seminiferous tubules, which then mature in the epididymis. During ejaculation, sperm travel through the vas deferens, mixing with seminal fluid to form semen, which is then expelled through the urethra.

The female reproductive system, conversely, operates on a cyclical basis, preparing for potential fertilization and pregnancy. Ovaries release one mature oocyte per month, which, if fertilized, can implant in the uterus. If fertilization does not occur, the uterine lining is shed during menstruation.

Reproductive Health

The development and function of the reproductive systems are susceptible to various disorders. In males, cryptorchidism (undescended testes) can lead to infertility if not corrected. In females, conditions like polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) can disrupt normal hormonal cycles, affecting fertility.

Conclusion

The development of the male and female reproductive systems is a marvel of biological engineering, involving a symphony of genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors. From a shared embryological pathway, these systems diverge to form structurally and functionally distinct organs, ensuring not only the survival of the individual but the continuation of the species.

As science advances, our understanding of these complex processes continues to grow, offering new insights into reproductive health and potential treatments for disorders that have challenged humans for centuries.

Read more: