Musculoskeletal Examination- An orthopedic nurse is a nurse who specializes in treating patients with bone, limb, or musculoskeletal disorders. Nonetheless, because orthopedics and trauma typically follow one another, head injuries and infected wounds are frequently treated by orthopedic nurses.

Ensuring that patients receive the proper pre-and post-operative care following surgery is the responsibility of an orthopedic nurse. They play a critical role in the effort to return patients to baseline before admission. Early detection of complications following surgery, including sepsis, compartment syndrome, and site infections, falls under the purview of orthopedic nurses.

Musculoskeletal Examination

The two primary subfields of orthopedic nursing are unplanned and elective surgery. Thus, elective surgery is when a patient’s quality of life is improved by a limb replacement, such as a hip or knee replacement, that has been detected during routine checkups.Some patients suffer an unanticipated injury, like a fractured hip, maybe while out for a walk. Within 48 hours of arriving at A&E, they will probably be clerked, admitted to an orthopedic ward, and undergo surgery.

A) Presenting complaints:

1) Pain:

- Determine whether the pain originates from a joint (arthralgia), muscle (myalgia) or other soft tissue structure.

- The site may be well localized and suggest the diagnosis, e.g. the first metatarsophalangeal joint in gout If, however, pain is referred, it may be difficult to determine the exact source

- Is it present at rest or aggravated by movement? Pain caused by a mechanical problem is worse on movement and eases with rest.

- The onset and timing of pain give clues to the diagnosis. For instance, pain from traumatic injury is usually immediate but is also exacerbated by movement or if bleeding occurs into the affected joint haemarthrosis).

Assessing musculoskeletal pain (mnemonic SOCRATES)

- Site

- Onset

- Character

- Radiation

- Associated factors

- Timing (frequency, duration, periodicity)

- Exacerbating features (exercise, use, etc.)

- Severity

2) Stiffness: Establish what the patient means by stiffness:

- Is it a restricted range of movement?

- Difficulty moving, but with a normal range of movement? Painful movement?

- Ask whether stiffness is localized to a particular joint or is more generalized, as in ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis.

- If stiffness predominates over pain, suspect spasticity (increasing muscle contraction in response to stretch) or tetany (involuntary sustainedcontraction), and examine for the increased tone characteristic of an upper motor neurone 1 esion.

- Inflammatory arthritis presents with early morning stiffness that takes at least 1 hour to wear off with

activity. - Non-inflammatory, mechanical arthritis tends to occur after resting, and stiffness lasts only a few minutes on movement. There may be pain on movement. This typically

3) Redness (erythema) and warmth:

- Erythematic and warmth over a joint are seen in acute inflammatory arthritis.

- Erythematic is common in infective, traumatic and crystal-induced conditions.

- It is unusual in seropositive rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus, and if present may suggest coexisting joint infection.

4) Swelling:

- Establish the site, localization, extent and time course of any swelling.

- Swelling may be diffuse soft tissue oedema or localized and caused by a discrete collection of fluid in a joint, bursa or tendon sheath

- This process is even more rapid and severe if the patient is taking anticoagulants or has an underlying bleeding disorder, e.g. haemophilia. If avascular structures such as the menisci are torn or articular cartilage is abraded, a reactive effusion.

5) Weakness:

Weakness suggests a joint disorder, peripheral nerve lesion, e.g. median nerve compression in carpal tunnel syndrome, or muscle disease.

- Proximal weakness suggests a primary muscle disease such as immune-mediated inflammatorymuscle disease, e.g. dermatomyositis or polymyositis, or a non-inflammatory myopathy, e.g. secondary to chronic alcohol use, steroid therapy or thyrotoxicosis.

- Distal weakness is more likely to be neurological such as the peripheral neuropathy of thiamine or vitamin B12 deficiency, connective tissue disorders, or peroneal muscular atrophy (Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease).

- If the weakness is intermittent and worsens during activity, then consider myasthenia gravis

- Slowly progressive generalized weakness is a feature of motor neuron disease. Other primary muscle diseases include the heritable muscular dystrophies

6) Locking and triggering:

Locking is an incomplete range of movement at a joint because of an anatomical block. It may be associated with pain. Patients use ‘locking’ to describe a variety of problems, so establish precisely what they mean.

- True locking is a block to the usual range of movement caused by a mechanical obstruction (such as a loose body or torn meniscus) within the joint. This prevents the joint reaching the extremes of the normal range of movement. The patient may be able to ‘unlock’ the joint by trick manoeuvres.

- Sometimes when extending a finger from a flexed position there is a block to extension, which then ‘gives’ suddenly. This is triggering. It results from nodular tendon thickening or a fibrous thickening of the flexor tendon sheath. In adults it usually affects the ring or middle fingers. It can be congenital, usually affecting the thumb.

7) Deformity:

Acute deformity may occur when there is a fracture, dislocation, or alteration of the external skin contour due to swelling, e.g. haemarthrosis or intramuscular haematoma

- Chronic joint deformity results in malalignment of the bones forming the joint, or malapposition of the joint surfaces which may be partial (subluxation) or complete (dislocation).

- Establish if the joint deformity is fixed or mobile (passively correctable). Extra-articular manifestations: Inflammatory arthritis is commonly associated with extra-articular features. Extra-articular manifestations: Inflammatory arthritis is commonly associated with extra-articular features.

8) Extra-articular manifestations:

Inflammatory arthritis is commonly associated with extra-articular features.

- The pattern of the joint condition(symmetric/asymmetric/flitting) and

- extent (mono-, oligo-, or polyarthritis) may suggest both the diagnosis and the extra-articular features to be sought.

B) Past history:

Note any past history that might contribute to the complaint, e.g.

- Pain and restricted movement in a joint that had been dislocated.

- Identify co-morbidfactors, diabetes mellitus, steroid therapy, ischaemic heart disease, stroke and obesity.

C) Drug history: Many drugs have side-effects that may either worsen or precipitate musculoskeletal conditions

D) Family history: A single gene defect (monogenic inheritance) is found in peroneal muscular atrophy (Charcot- Marie-Tooth disease), osteogenesis imperfecta, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan’s syndrome and the muscular dystrophies. Osteoarthritis, osteoporosis and gout are heritable in a variable polygenicfashion. Seronegative spondyloarthritis is more common in patients with HLA B27 Rheumatoid arthritis is also associated with a familialtendency.

E) Environmental, occupational and social histories: These may be relevant in the aetiology and in assessing how the patient is affected. They may also lead to litigation, e.g. in occupation-related complaints such as repetitive strain injury, hand-vibration syndrome, and fatigue fractures. Army recruits, athletes and dancers are at particular risk of fatigue fractures.

Some conditions are seen in certain ethnic groups: sickle cell disease may present with bone and joint pain;osteomalacia is more often seen in Asian patients; bone and joint tuberculosis is more common in African and Asian patients. Take a sexual history (since sexually transmitted disease may be relevant, e.g. Reiter’s syndrome, gonococcal arthritis and hepatitis B.) identifies social factors that may contribute to musculoskeletal conditions.

THE PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

1) THE SPINE

a) Cervical spine:Ask the patient to remove enough clothing for you to see the neck and upper thorax, then to sit on a chair.

i. Look: Face the patient. Observe the posture of the head and neck and note any abnormality or deformity, e.g. loss of lordosis (usually due to muscle spasm)

ii. Feel : Note any tenderness in the spine, trapezius, interscapular and paraspinal muscles. Move:Assess active movements first Ask the patient to:

- ‘Put your chin onto your chest’ to assess forward flexion. The normal range is 0 to 80°. Record a decreased range as the chin-chest distance.

- ‘Look upwards at the ceiling as far back as you can’ to assess extension. The normal range is 0 to 50°. Thus the total flexion-extension arc is usually around 130°.

- ‘Put your ear onto your shoulder’ to assess lateral flexion. The normal range is 0 to 45°.

- ‘Look over your right/left shoulder’. The normal range of lateral rotation is 0 (neutral) to 80°.

b)Thoracic spine: Ask the patient to undress to expose the neck, chest and back.

i. Look With the patient standing, inspect posture from behind, the side and the front, noting any deformity, e.g. rib hump or abnormal curvature.

ii. Move: Ask the patient to sit with arms crossed. Ask the patient to twist round and look at you.

c)Lumbar spine:

i. Look: Examine the patient standing. Look for obvious deformity such as decreased/increased lordosis.

ii. Feel: Palpate the spinous processes and paraspinal tissues. Note the overall alignment and focal tenderness.

iii. Move:

- Flexion: Ask the patient to try to touch his toes with his legs straight. Record how far down the legs the patient can reach; a certain amount of such movement is dependent on hip flexion.

- Extension: Ask the patient to straighten up and lean back as far as possible (normal 10-20° from neutral erect posture).

2) The shoulder:

a) Look:

Examine the whole shoulder girdle front and back including the axilla for:

i. Deformity. The deformities of anterior glenohumeral and complete acromioclavicular joint dislocation

ii. Swelling. In dislocations, proximal humeral fractures, haemarthrosis and inflammatory conditions.

iii. Muscle wasting especially of the deltoid, supraspinatus and infraspinatus. Wasting of supraspinatus or infraspinatus usually indicates a chronic tear of their tendons.

iv. The size and position of the scapula (i.e. elevated or depressed). A small elevated scapula occurs in the rare conditions of Sprengel’s shoulder and Klippel-Feil syndrome. ‘Winging’ of the scapula occurs with paralysis of the nerve to serratus anterior

b) Feel:

i) Start at the sternoclavicular joint and palpate along the clavicle to the acromioclavicular joint.

ii) Clavicular fractures and acromioclavicular joint injuries are accompanied by deformity and local tenderness.

iii) Palpate the acromion and coracoid (2 cm inferior and medial to the clavicle tip) processes, the scapula spine and the biceps tendon in the bicipital groove.

iv) Palpate the supraspinatus tendon by extending the shoulder to bring supraspinatus anterior to the acromionprocess. Tenderness is present with ligamentous tears and calcific tendonitis.

c)Move:

Stand behind the patient.

i. Ask the patient to put both hands behind the head, then to put the arms down and to reach behind the back to touch the shoulder blades.

ii. Range of movement. Determine the range of active and passive movement:

iii. Ask the patient to flex and extend the shoulder as far as possible.

iv. To test abduction ask the patient to lift the arm away from the side of the body. 50-70% of abduction occurs at the glenohumeral joint (the rest occurs with movement of the scapula on the chest wall), but this increases if the arm is externally rotated.

v. Measure internal and external rotation with the patient’s arm by the side of the body and the elbow flexed at 90°. Internal rotation is expressed as the highest lumbar spinous process that the thumb can reach.

vi. Assess the ability of the deltoid to abduct against resistance – compare side with side.

vii. Rotator cuff problems: Ask the patient to abduct the arm from the side of the body against resistance. If abduction cannot be initiated or is painful this suggests a rotator cuffproblem.

viii. Impingement: Test for a painful arc by passively abducting the arm fully and asking the patient to lower (adduct) it slowly. A painful arc occurs between 60°and 120° of abduction. If the patient cannot initiate abduction, passively abduct the patient’s internally rotated arm to 30-45° while placing your hand over the scapula to confirm there is no scapular movement.

ix. Ligamentous tears and injuries. To test the component muscles of the rotator cuff, neutralize the effect of

other muscles crossing the shoulder. Discrepancy between active and passive ranges suggests a tendinous tear – in particular with subscapularis where there may be an excessive range of passive internal rotation. x. Bicipital tendonitis: Palpate the bicipital tendon in its groove noting any tenderness. Ask the patient to supinate the foream, and then flex the arm against resistance. Pain is produced in bicipital tendonitis.

3) The Elbow :

The elbow joint has humero-ulnar, radio-capitellar, and superior radio-ulnar articulations.

Examination sequence of elbow

a) Look

i.At the overall alignment of the extended elbow.

ii. For swelling, bruising, and scars.

iii. For evidence of synovitis between the lateral epicondyle and olecranon.

iv. For olecranon bursitis.

v. For rheumatoid nodules on the proximal extensor surface of the forearm.

b) Feel

i. The bony contours of the lateral and medial epicondyles and olecranon tip, defining an equilateral triangle with the elbow flexed at 90°.

ii. Synovitis feels spongy or boggy when the elbow is fully flexed. Feel for sponginess on either side of the olecranon and ask about tenderness.

iii. Focal tenderness, over the lateral or medial epicondyle. When isolated to one site this may indicate ‘tennis'(lateral) or ‘golfer’s’ (medial) elbow. Tenderness at multiple sites may be part of fibromyalgia syndrome.

iv. For bursae – fluid-filled sacs, usually soft but if acute or infected may be firm.

v. For rheumatoid nodules on the proximal extensor surface of the forearm.

c) Move

- Assess the extension-flexion arc. Ask the patient to touch the shoulder on that side and then straighten the elbow as far as possible. The normal range of movement is 0-145°; a range less than 30-110° will cause functional problems.

- To assess supination and pronation ask the patient to put the elbows by the side of the body and flex them to90°. Now ask the patient to turn the hands upwards to face the ceiling(supination normal range 0-90°) andthen downwards to face the floor (pronation – normal range 0-85°).

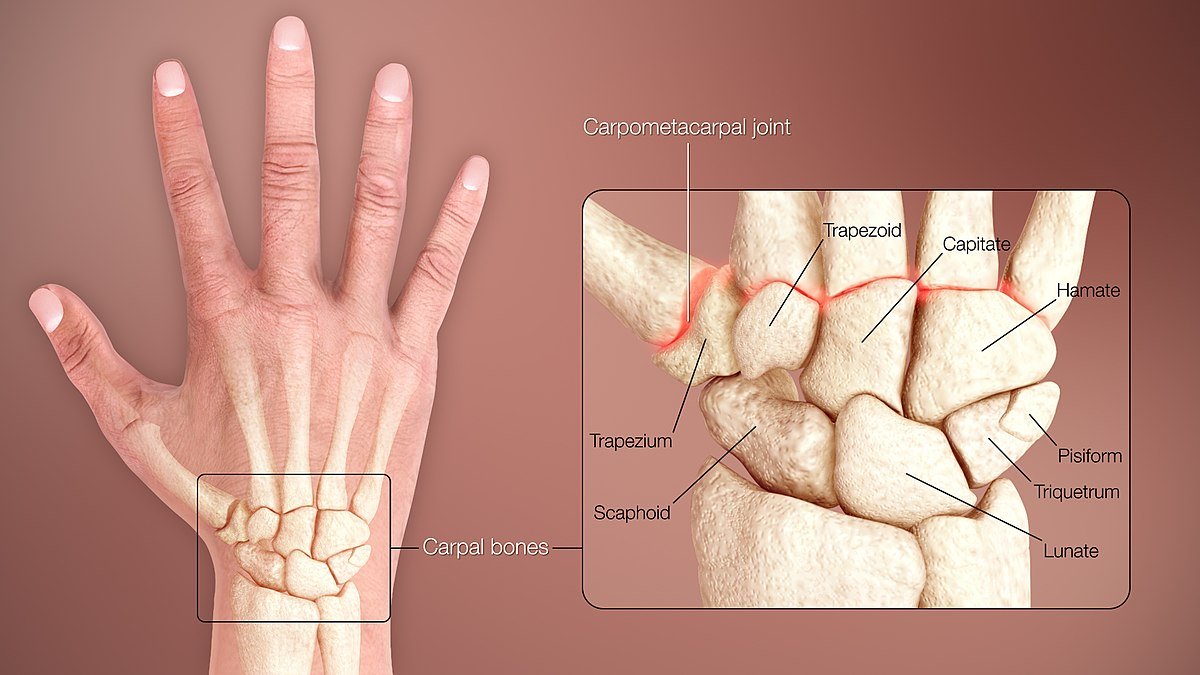

4)The hand and wrist:

a) Look

- Colour change. Erythema suggests acute inflammation caused by soft tissue infection, septic arthritis,

- Look for distal radius fracture for Colles fracture

- Swelling. Swelling at the MCP and/or IP joints suggests synovitis.

- Deformity: The fingers are long and thin in Marfan’s Phalangeal fractures may produce rotational deformity.

- Boutonnière (or button-hole) deformity – a flexion deformity at the PIP joint with hyperextension at the DIP joint

- ‘Swan neck’ deformity –

- Ulnar deviation of the MCP joints is typical of rheumatoid arthritis.

- Dupuytren’s contracture affects the palmar fascia,

- Extra-articular signs.

- Palmar erythema.

- Nail changes, e.g. pitting (psoriasis) and loosening of the nail from its bed (onycholysis) in psoriaticarthritis

b) Feel

- Hard swellings suggest bony outgrowths (osteophytes)

- Soft swellings suggest synovitis.

- To detect crepitus, place your index finger across the patient’s fully extended fingers and ask the patient to open and close the fingers.

c) Move

- Active movements of the hand:

- Ask the patient to make a fist, then extend (stretch out) the fingers fully. To test the power of grip, ask the patient to squeeze two of your fingers inserted from the thumb side into the palm of the patient’s hand.

- To assess extension, ask the patient to put the palms of the hands together and extend the wrists fully prayer sign’ (normal is 90° of extension)

- To assess flexion, ask the patient to put the backs of the hands together and flex the wrists fully ‘reverse prayer sign’ (normal 90° of flexion)

5) The hip:

Examination sequence: Patients should undress to their underwear and remove socks and shoes. You should be able to see the iliac crests so you may need to pull down the top of their underpants.

a) Look

- Is there shoulders are parallel to the ground and placed symmetrically over the pelvis

- Is there a pelvic tilt (which may mask a hip deformity or true shortening of one leg)

- Is there deformities of hip, knee, ankle, foot

- Is there muscle wasting (from polio or disuse secondary to arthritis)

- Is the spine is straight or curved laterally (scoliosis)

- Around the hip, whether there are scars, sinuses, dressings, skin changes.

6) Femur and tibia:

a) Feel

- Tenderness on palpation over the greater trochanter suggests trochanteric bursitis.

- Tenderness over the lesser trochanter and ischial tuberosity is common in sporting injuries due to strains of the iliopsoas and hamstring muscle insertions respectively.

b) Move

- Flexion. Place your left hand under the back (to detect any masking of hip movement by movement of the pelvis and lumbar spine and check the range of flexion of each hip in turn (normal 0-120°).

- Abduction and adduction. Stabilize the pelvis by placing your left hand on the opposite iliac crest. With your right hand abduct the extended leg until you feel the pelvis start to tilt (normal 45°). Test adduction similarly by crossing one leg over the other and continuing to move it medially (normal 25°).

- Internal and external rotation. Test with the leg in full extension by rolling the leg on the couch and using the foot to indicate the range of rotation. Then test with the knee (and hip) flexed at 90°.

- Extension. Ask the patient to lie face down on the couch. Place your left hand on the pelvis to detect any movement. Lift each leg in turn to assess the range of extension (normal range 0-20°)

Examine this patient with acute hip pain felt in the groin :

i. Ask the patient to walk and observe gait from the front and side.opamin

ii. Perform Trendelenburg’s test.

iii. Measure leg lengths.

iv. Examine movements at the hip in all directions (abduction/adduction, internal/external rotation, flexion).

7) The knee:

a) Look

- Observe the patient walking and standing as described for gait.

- Ask the patient to lie face up on the couch. Both legs should be fully exposed. Look for:

- Scars, sinuses, redness or rashes.

- Posture and common deformities, genu valgum (knock-knee) or genu varum (bow-legs).

- Muscle wasting: quadriceps wasting is almost invariable with inflammation or chronic pain erosity. Leg length discrepancy

- Flexion deformity: if the patient lies with one knee flexed this may be caused by a hip, knee or combined problem

- Swelling: an enlarged prepatellar bursa (housemaid’s knee) and any effusion of the knee joint – a largeeffusion is seen as a horseshoe-shaped swelling above the knee. Swelling extending beyond the joint margins suggests infection, major injury or rarely tumour.

- Baker’s cyst: bursa enlargement in the popliteal fossa

b) Feel:

- Warmth. Feel the skin comparing both sides

- Effusion:

- The patellar tap. With the knee extended, empty the suprapatellar pouch by sliding your left hand down the thigh until you reach the upper edge of the patella. Keep your hand there and with the finger tips of your right hand press down briskly and firmly over the patella (Fig. 10.47). In a moderate-sized effusion you will feel a tapping sensation as the patella strikes the femur. You may feel a fluid impulse in your left hand.

- The ‘ripple test’: With the knee extended and the quadriceps muscles relaxed, empty the suprapatellar pouch as for the patellar tap. Then, with your fingers extended, stroke the medial side of the joint. Now stroke the lateral side of the joint and watch the medial side for a bulge or ripple as fluid reaccumulates on that side.

- Joint lines. Feel the tibial and femoral joint lines.

c) Move:

- Active flexion and extension. With the patient supine:

- Ask the patient to flex the knee up to the chest and then extend the leg back down to lie on the couch. Feel for crepitus between the patella and femoral condyles suggesting chondromalacia patellae (especially in younger female patients) or osteoarthritis. If there is a fixed flexion deformity of 15° and flexion is possible to 110° record this as a range of movement of 15-110°.

- Ask the patient to lift the leg with the knee kept as straight as possible.

- Passive flexion and extension. Normally the knee can extend so that femur and tibia are in longitudinal alignment.

Special tests:

i) Tests for meniscal tears: Meniscal tears in younger sporting patients are often the result of a specific injury, most commonly a twisting injury to the flexed weight-bearing leg. In middle-aged patients degenerative horizontal cleavage of the menisci is common and there may be no history of trauma, Associated well-localized joint-line tenderness is common. Meniscal injuries are commonly associated with small effusions especially on weight-bearing or after exercise. There may be localized joint-line tenderness.

ii) Meniscal provocation test.

Medial meniscus. Passively flex the knee fully, externally rotate the foot and abduct the upper leg at the hip keeping the foot towards the midline. Then extend the knee smoothly. In medial meniscus tears a click or clunk may be felt or heard accompanied by discomfort.

Lateral meniscus. Passively flex the knee fully, internally rotate the foot and adduct the leg at the hip Then extend the knee smoothly. In tears of the lateral meniscus a click or clunk may be felt or heard accompanied by discomfort.

Squat test: Ask the patient to squat, keeping the feet and heels flat on the ground. If the patient cannot do this it indicates incomplete knee flexion on the affected side. This may be caused by a tear of the posterior horn of the menisci. The extreme range of knee flexion may also be tested with the patient face down on the couch, which makes for easy comparison with the contralateral side.

Examine this patient who complains of pain in the knee aggravated by walking

i. Ask the patient to walk and observe gait and movement of the knee from the front and side.

ii. Ask the patient to lie on the couch and expose both legs.

iii. Look at the lower limbs for redness, scars, muscle wasting, deformity, swollen bursae, etc. Feel both knees with the back of your hand for temperature difference warm in septic arthritis and haemarthrosis.

iv. 4. Palpate for knee effusion – found in septic arthritis, trauma, haemarthrosis.

v. Feel for tenderness over joint lines and soft tissues.

vi. Assess active and passive movements at both knees – note crepitusulas cond

vii. Examine collateral and cruciate ligament stability.

8) The ankle and foot:

Ask patients to remove their socks and shoes.

a) Look:

- Examine the soles of the shoes for any abnormal patterns of wear.

- Gait. Observe as described previously. In particular, look for:

- Increased height of step indicating ‘foot-drop’

- Ankle movement (dorsi-/plantar flexion)

- Position of the foot as it strikes the ground (supinated/pronated)

- Hallux rigidus.

- With the patient standing observe:

- From behind: how the heel is aligned (valgus/varus)

- From the side: the position of the midfoot, looking particularly at the longitudinal medial arch. This may be flattened (pes planus – flat foot) or exaggerated (pes cavus). If the arch is flattened, ask the patient to stand on tip-toe, which will restore the arch in a mobile deformity, but not in one with a structural basis.

- A splay-foot is one in which there is widening of the foot at the level of the metatarsal heads often associated with MTP joint synovitis.

- Examine the ankle and foot for scars, sinuses, swelling, bruising, callosities (an area of thickened skin at a site of repeated pressure), nail changes, oedema, deformity and position (e.g. fixed plantar flexion or foot- drop).

- The toes. Look for deformities of the great and other toes

- Hallux valgus is very common

- Swelling of the entire digit ‘sausage toe’ (dactylitis) is characteristic of psoriatic arthropathy.noithatod Claw toes result from dorsiflexion (hyperextension) at MTP joints and plantar flexion at PIP and DIP joints.

- Hammer toes are due to dorsiflexion at MTP and DIP joints and plantar flexion at PIP joints.

- Mallet toes describes plantar flexion at DIP joints.

b) Feel:

i. Feel the ankle and foot for focal tenderness and heat. In an acute ankle injury it is particularly important to palpate the proximal fibula, both malleoli, the lateral ligament and base of the fifth metatarsal.

ii. Gently compress the forefoot.

c) Move:

i. Assess the range of plantar and dorsiflexion at the ankle and inversion/eversion of the forefoot by asking the patient to perform these movements.

ii. Ankle dorsiflexion/plantar flexion. Grip the heel with the cup of your left hand from below, with the thumb and index finger on the malleoli. Put the foot through its arc of movement (normal range 15°dorsiflexion to 45° plantar flexion). If dorsiflexion is restricted, assess the contribution of gastrocnemius (which functions across both knee and ankle joints) by measuring ankle dorsiflexion with the knee extended and flexed. If more dorsiflexion is possible with the knee flexed, this suggests a gastrocnemius contracture.

iii. Foot inversion/eversion. The subtalar joint may be examined in isolation by placing the foot into dorsiflexion to stabilize the talus in the ankle mortice, then moving the heel into inversion (normal 20°) and eversion (normal 10°). This can also be performed with the patient lying face down with the knee flexed. The combined midtarsal joints are then examined by fixing the heel with your left hand andmoving the forefoot with your right hand into dorsiflexion, plantar flexion, adduction, abduction, supination and pronation.

Special tests :

- Achilles tendon: Ask the patient to kneel with both knees on a chair. Palpate the gastrocnemius and Achilles tendon for focal tenderness and soft tissue swelling. Achilles tendon rupture is often palpable as a discrete gap in the tendon about 5 cm above the calcaneal insertion.balan

- Thomson’s (Simmond’s) test: Squeeze the calf just distal to the level of maximum circumference. If the Achilles tendon is intact, plantar flexion of the foot will occur