Uterine Inversion – This course is designed to understand the care of pregnant women and newborn: antenatal, intra-natal and postnatal; breast feeding, family planning, newborn care and ethical issues, The aim of the course is to acquire knowledge and develop competencies regarding midwifery, complicated labour and newborn care including family planning.

Uterine Inversion

Uterine inversion:

Uterine inversion, either partial or complete, is a rare but serious obstetric complication. It usually occurs in the second stage of labour and is a life-threatening complication requiring prompt diagnosis and definitive management.

Or

Uterine inversion is a serious but rare complication of childbirth in which the uterus literally turns inside out after the baby is delivered. When this happens, the top of the uterus (the fundus) comes through the cervix or even completely outside the vagina. It occurs in about 1 in 3,000 births.

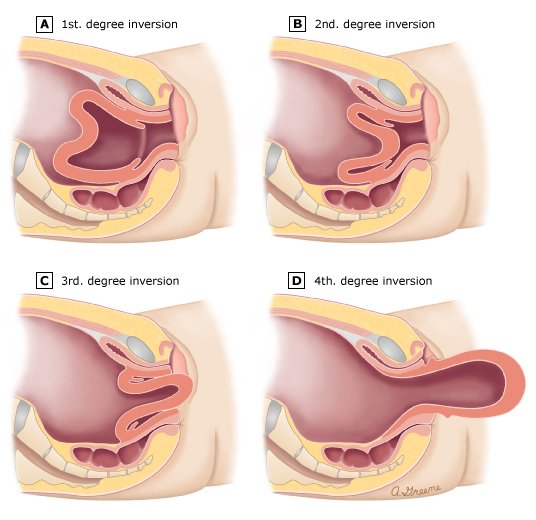

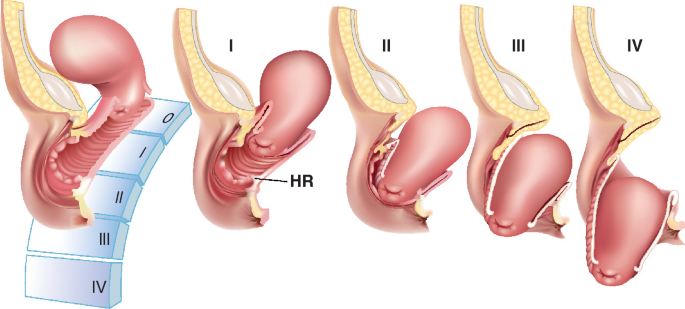

Description of the degree of inversion:

1. First-degree the inverted fundus extends to, but not through, the cervix.

2. Second-degree the inverted fundus extends through the cervix but remains within the vagina.

3. Third-degree the inverted fundus extends outside the vagina.

4. Total inversion the vagina and uterus are inverted.

Causes/factors associated with uterine inversion:

The exact cause of uterine inversion is not well understood. However, the following risk factors are associated with it:

- Labor lasting longer than 24 hours.

- A short umbilical cord.

- Prior deliveries.

- Use of muscle relaxants during labor.

- Abnormal or weak uterus.

- Previous uterine inversion.

- Placentaaccreta, in which the placenta is too deeply embedded in the uterine wall.

- Fundal implantation of the placenta, in which the placenta implants at the very top of the uterus.

Or (Another answer)

Various factors have been linked to puerperal uterine inversion, although there may be no obvious cause. Identified factors include:

- Short umbilical cord.

- Excessive traction on the umbilical cord.

- Excessive fundal pressure prior to placental separation.

- Premature cord traction prior to placental separation

- Fundal implantation of the placenta.

- Retained placenta and abnormal adherence of the placenta.

- Chronic endometritis.

- Vaginal births after previous caesarean section.

- Multiparity.

- Uterine atony.

- Exceptionally large fetus.

- Polyhydramnios.

- Precipitate labour.

- Previous uterine inversion.

- Antepartum use of certain drugs such as magnesium sulfate (drugs promoting tocolysis).

- Structural anomaly of the uterus, such as unicornuate uterus.

- Connective tissue disorders such as Marfan’s syndrome.

Poor management of labour may be a cause in up to 75% of cases, especially when the rate is high. Active management of the third stage of labour may reduce the incidence. In the non-obstetric uterine inversion, a fundally placed tumour is usually the cause.

Diagnosis methods of uterine inversion:

Prompt diagnosis is crucial and possibly lifesaving. Some of the signs of uterine inversion could

include:

1. The uterus protrudes from the vagina.

2. The fundus doesn’t seem to be in its proper position when the doctor palpates (feels) the mother’s abdomen.

3. The mother experiences greater than normal blood loss.

4. The mother’s blood pressure drops (hypotension).

5. The mother shows signs of shock (blood loss).

6. Scans (such as ultrasound or MRI) may be used in some cases to confirm the diagnosis.

Clinical features of uterine inversion:

Possible symptoms include:

- The uterus is protruding from the vagina.

- The uterus doesn’t feel like it’s in the right place.

- Massive blood loss or a rapid decrease in blood pressure.

The mother may also experience some of the following symptoms of shock:

- lightheadedness

- dizziness

- coldness

- tiredness

- shortness of breath

Investigations of uterine inversion:

- If not clinically obvious, ultrasound can be used to identify the inversion.

Treatment of uterine inversion:

Treatment options vary, depending on the individual circumstances and the preferences of the hospital staff, but could include:

1. Attempts to reinsert the uterus by hand.

2. Administration of drugs to soften the uterus during reinsertion.

3. Flushing the vagina with saline solution so that the water pressure ‘inflates’ the uterus and props it back into position (hydrostatic correction).

4. Manual reinsertion of the uterus while the woman is under general anaesthetic.

5. Abdominal surgery to reposition the uterus if all other attempts to reinsert it have failed.

6. Antibiotics to reduce the risk of infection.

7. Intravenous liquids.

8. Blood transfusion.

9. Intravenous administration of oxytocin to trigger contractions and stop the uterus from inverting again.

10. Emergency hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus) in extreme cases where the risk of maternal death is high.

11. Close monitoring in intensive care for a few days, if necessary.

Differential diagnosis of uterine inversion:

1. Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) due to more common causes.

2. Prolapse of a uterine tumour.

3. Gestational trophoblastic disease,

4. Occult genital tract disease.

5. Marked uterine atony.

6. Undiagnosed second twin.

Management of uterine inversion: The important principles are:

- Treatment should follow a logical progression.

- The Hypotension and hypovolaemia require aggressive fluid and blood replacement.

four components of management to be instigated at the same time are:

1. Communication.

2. Resuscitation.

3. Monitoring and investigation.

4. Measures to arrest the bleeding.

- Immediate uterine repositioning is essential for acute puerperal inversion.

Measures to reposition the uterus may include:

❖ Preparing theatres for a possible laparotomy.

❖ Cautious administration of tocolytics to allow uterine relaxation; however, this may aggravate haemorrhage:

- Nitroglycerin (0.25-0.5 mg) intravenously over 2 minutes; or

- Terbutaline 0.1-0.25 mg slowly intravenously; or

- Magnesium sulfate 4-6 g intravenously over 20 minutes.

❖ Attempting prompt repositioning of the uterus. This is best done manually and quickly, as delay can render repositioning progressively more difficult. Reposition the uterus (with the placenta if still attached) by slowly and steadily pushing upwards towards the umbilicus, commonly referred to as Johnson’s method. Maintain bimanual uterine compression and massage until the uterus is well contracted and bleeding has stopped.

❖ If this fails, hydrostatic replacement should be attempted under spinal or general anaesthetic:

- O’Sullivan’s technique involves an infusion of warm saline into the vagina, making a water seal with the operator’s hand and the vulva. Successful modifications of this technique, including using a vacuum cup to obtain a better vaginal seal and using a transurethral resection of prostate (TURP) set to increase the hydrostatic pressure, have been reported.

- An SOS Bakri tamponade balloon has also been successfully used to replace the inverted uterus and to maintain its position.

❖ If this is unsuccessful, a surgical approach is required. Laparotomy for surgical repositioning is more usual (find and apply traction to the round ligaments). Incision of the cervical ring may be required. A vaginal or even laparoscopic approach can be used, although this is more likely in the non-obstetrie inversion.

❖ If this is unsuccessful, hysterectomy, which may be life-saving, is the final option.

Or (Another Management)

The two cornerstones of management are:

1. Replacement of the uterus and

2. Resuscitation from the hemorrhage.

❖ Discontinue uterotonic therapy.

❖ Notify the anesthesia team so that adequate pain relief can be achieved and preparations can be made should general anesthesia or operative intervention be required.

❖ Prepare for large hemorrhage by (1) establishing two sites of IV access, at least one of which should be large bore, and (2) ordering blood products and laboratory studies (hemoglobin, platelet count, coagulation indices).

❖ Replacement of the uterus should be attempted immediately, as it is most easily achieved before the cervix and lower uterine segment begin to contract.

❖ Administer uterine relaxants. Start with what is immediately available, such as terbutaline (0.25mg subcutaneously), nitroglycerin (50-500 micrograms intravenously) or magnesium sulfate (2-6 grams intravenously over 15 minutes). If these are unsuccessful then halogenated anesthetics (halothane, enflurane, etc) can be utilized.

❖ Apply steady pressure to the uterus to push it back through the vagina and cervix. Generally the portion that inverted last, closest to the cervix, should be replaced first and the uterine fundus replaced last.

❖ If the placenta is still attached, removal should not be attempted until the uterus has been restored to its appropriate position.

❖ In refractory cases laparotomy is the next step. Methods that have been described to correct the inversion surgically include: (1) serial clamping and upward traction on the round ligaments to elevate the fundus (Huntington procedure); and (2) incision along the posterior wall of the uterus in the area of the constriction and then manual repositioning of the fundus (Haultain procedure).

❖ Once the uterus is repositioned:

- Palpate for evidence of uterine rupture and maintain a hand within the cavity until the uterus feels contracted.

- Initiate oxytocin or alternate uterotonic such as methylergonovine or carboprost to improve uterine tone in order to decrease the risk for recurrent inversion and minimize further blood loss.

- Insert Foley catheter to monitor urine output given large blood loss.

❖ The utility of antibiotics in preventing infectious morbidity is not well established, so use should be for reserved for women with other obstetric indicaitons for antibiotic use.

❖ Transfusion of blood products should be based upon typical clinical considerations.

Complications of uterine inversion:

Some complications of uterine inversion:

Complications include:

❖ Endomyometritis, and

❖ Damage to intestines, ureters or uterine appendages.

❖ Death can occur quickly if the condition is not recognised.

Or

Complications due to condition:

The primary complication is hemorrhage and its attendant risks

- shock.

- multi-organ damage,

- Sheehan syndrome,

- need for hysterectomy

The risk for requiring a blood transfusion is nearly 50% in some series. Left untreated, the condition can result in persistent blood loss and tissue necrosis.

Complications due to management:

The risks faced by the patient during treatment of uterine inversion include those risks associated with general anesthesia and with transfusion of blood products.